“There was a glory and a wonder and a mystery about that mad ride which I felt keenly… until I had to offer prayers for the safety of the train… I knew we should damage something in the end—the sombre horrors of the gorge, the rush of the jade-green water below, and the cheerful tales told by the conductor made me certain of the catastrophe.”

Rudyard Kipling, on his visit to the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, 1900

I was watching Cops on the couch of Suzie’s basement, my face cooking at a low burn under the blur of the Vicodin, when I had two realizations:

One, I realized the episode of Cops I was watching was a rerun. It’s not a good sign when you start recognizing episodes of Cops.

Two, I hadn’t used the bathroom in a week.

They call it opioid-induced constipation. Too many pills, and wires get crossed down there. Nothing will get you moving, not if you had a gun to your forehead. I had been on a heavy dose ever since the attack. Without the pills, my face burned. At night, my dreams burned. I dreamed of that dog chewing its way through the pasteboard bedroom door of the RV.

It all began on Labor Day. The end of summer. A big deal in a mining town. Some friends from the mine and their girlfriends had rented an RV. There was Shep, who rode the Durango Freight Line, picking up coal every month. Griff was there, too, from the mine survey team. He’d served a tour in Iraq, came back with a Purple Heart. We packed six cases of cheap beer, threw the old RV into drive, and made it waddle its way up into the cliffs of the Black Canyon.

A soft sting of beer hung in the air. Uncle Kracker played loud and clear from a repeater in Montrose, our wives and girlfriends swayed to the country rhythm in low-cut jeans, and we watched the last rays of sunset filter between the shadowed canyon walls.

And there was a dog. Sikes, that was his name. From Oliver Twist. I was watching the sunset, feeling the rhythm of a country song, when I heard the clatter of paws coming down the RV stairs. A brown blur tore past me through the gravel, and crawled under the RV.

“Oh gosh darn” said Suzie. My then-girlfriend pouted at the RV door. “I was just gettin’ my camera on the bed and he ran out. Could you go get him?”

I looked back cross the canyon. The sun had gone out. The Black Canyon doesn’t get much light, maybe a half-hour a day. This evening we’d timed it perfect. But now the canyon really was black. I squatted and peeked under the RV.

“I can’t see him” I said. “Maybe he’ll come out on his own.”

“You need to go check on him” said Suzie.

“In a minute” I said. I sucked on the beer can for a few more drops. I did not want to go under that RV.

“Come oooon!” she whined. “Maybe he’s hurt or something. God, you’re mean, you know that?”

I tossed the can away and crawled under the RV. Now I think this is how airheads like Suzie survive. The squeaky wheel gets the oil.

Suzie had adopted Sikes after he was rescued from a dog-fighting ring. The courts said Sikes was rehabilitated, but even then, he was no cuddler. Sikes was one of those dogs you didn’t look in the eyes. It’s hard dating a woman when her 90-pound dog was telling you to get off his couch.

I’d be fine as long as I didn’t look into his eyes. I couldn’t see anything but some dim light off the undercarriage. The country beat kept thumping outside.

“Find ’im yet?” yelled Suzie.

“No, not yet” I said. “Can’t see anything.” I could hear Sikes panting somewhere, and Uncle Kracker thumping low. The panting stopped. I stopped crawling. I heard a low growl, dry and hot under the RV. My muscles locked. My eyes faced forward. The growl went on and on, from deep to a guttural shudder.

Where the hell was that dog?

I thought I felt it more in my right ear, so I didn’t dare turn right.

Suzie’s voice reached me. “What’s taking so long?”

I didn’t reply. I didn’t move. I heard someone say, “Bye, Sooz.” A car door closed, and a Jeep started up. As it swung out of the parking lot, the headlights came up behind me.

What I saw stiffened me out into stone.

Directly ahead of me were two orbs of glowing light, hanging in space.

In the pitch dark, I couldn’t see in front of me, but dogs can see in the dark. I had been staring into Sikes’ eyes the whole time.

The last thing I remember was the roar that dog made as the eyes lunged at me. It seemed to rise from hell itself. Shep and Griff heard my screams. It took an hour to drive down to the Montrose hospital on a coiling mountain road.

As I lay on the RV sofa, Shep yelled at Griff to keep the RV steady.

Something kept tickling my face. “Get this thing off me” I moaned. I tried brushing it away, but couldn’t. It was my lips.

After the operation, and I could walk on my own two feet, I shuffled over in my hospital gown to the bathroom. It looked like someone had tossed uncooked bacon on my face. When I’d become conscious enough, I’d asked the doctors why my face burned. They mentioned nerve damage. Apparently, I was lucky, I could have had facial paralysis and needed a bib for the drooling.

Before the attack, I’d been working at the Dunwich Coal Mine, on the other side of the valley. It took me six months to earn my license for the heavy machinery, but I couldn’t work there on my current dosage. A twenty-ton bore will kill you in a heartbeat. They were going to transfer me to the mine’s front office, doing data entry, but I think my face scared some of the women. Now, I couldn’t go outside without someone gawking or choking on a bite of food when they saw me. I stayed in and wolfed pills and pizza rolls.

I’d started off looking for work, believe me, but Dunwich is a tiny mining town at 7,000 feet along the Gunnison River. In Dunwich, there was the coal mine, the truck stop, the car wash, the dollar store, and the bar. That was about it, unless you drove 45 minutes on Highway 92 to Hotchkiss or Delta, with twenty feet of snow on the way. I’ll just say I held out longer on the job hunt I thought I would.

Every morning, the moment my alarm clock rang, I woke to what felt like a landslide moving from my head on down. I leaped out of bed and skipped across the cold floor to the toilet. Nothing. The moment I pulled my boxers up and left the bathroom, the landslide feeling returned, that full-on panic, and I flew back to the crown. Ten minutes. Twenty minutes. I left the bathroom defeated. I looked into the mirror, sweat everywhere on my face but the scar tissue.

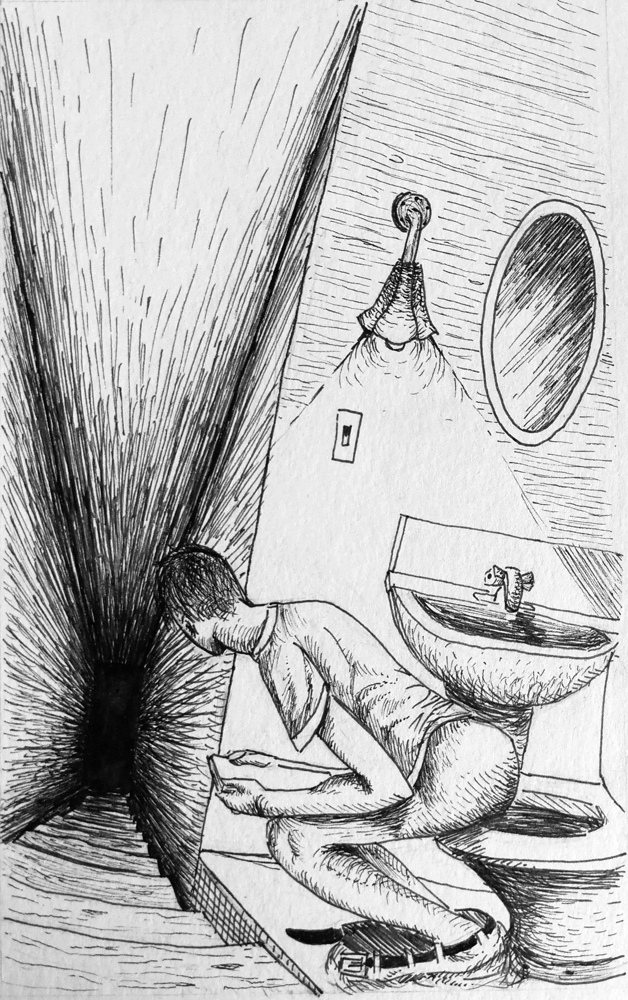

I moved into the bathroom. Pillows on the floor. My laptop, powered by a cord suspended in the air to reach, let me watch movies. I could stay in the bathroom for hours at a time. I tried squatting, yoga postures, laxatives, enemas, suppositories, sugar-free gummy bears, aerobics, caffeine, coffee grinds, and ultra-low-frequency subwoofers.

I tore through books of crossword puzzles and sudoku. I immersed myself in word searches and scrambled quotes.

I tried writing some work of my own, but I had to give that up quickly.

I had writer’s block.

Then my girlfriend broke up with me. She blamed me for getting her dog put down. She cried more for her monster than for what it did to my face.

This was a problem since I’d been living with her.

What do you do with no job and no home? I got back in my truck and drove up the forest road to Black Canyon. I hadn’t been back since the attack. Now that I was jobless, I’d come for ten hours at a time. I sat in the parking lot, watching the river wind pass the shadowed cliffs.

There was a deep menace in that canyon. The cliff walls rose so high that the sun never touched the river. Sometimes I got out and kicked my feet over the ledge of the cliff wall. It would take fifteen seconds to fall, a half-mile into the Gunnison rushing below me. I would just have to lean forward. It would be that easy. I took some pills to get my mind off my itching face and my aching guts. Then, as always, everything clicked, that urge returned.

I ran to the parking lot restroom, almost doubled over from the pain.

I yanked on the door. Locked.

“Uh, uh, occupied” came a voice.

“Hurry it up” I grunted.

“Juh-just a minute” the voice stammered.

I sucked in a shallow breath, telling myself I’d count down from ten. When I hit ‘two’ I pounded on the door.

“Come on!” I yelled. Who would dare waste their time in a public toilet? My fingers were reaching for the door handle, when I heard a voice behind me.

“Easy, buddy.”

I turned around to see an old man in hiking gear, a few decades past fashionable.

I was about to turn on the him, but my resolve crumbled away. The tears came fast, my throat choked out a wavery sputter.

“I think we were about headed back, don’t you?” the old man asked. I looked around, feeling the stares of every tourist in the lot. I had no idea what this man wanted, but I took my chance to leave.

Five minutes later, we were headed back down to the highway.

“I hike up from the lower lot on Wednesdays,” the man said. “Anyone with a gym membership, when you could be out here…” he waved an arm across the shadowed canyon walls, and twirled a finger next to his temple. He extended a hand.

“Chester’s the name” he said. “I don’t think we’ve crossed paths, I do some work around town.”

I took my left hand off the steering wheel to shake his.

“Listen, he continued, “I’m not sure what it’s like at home, but I’ll take a guess that you need a change of scene. I’m happy to let you stay in my guest bed for a bit.”

I sighed. “Any Bible readings involved in this deal?”

Chester shrugged. “I read a few verses in the morning. You can join if you like. I’ll be straight: my property needs some upkeep, and I’m too busy. I’m figuring free time isn’t your best friend right about now. It’d sure beat sitting on your ass all day, popping pills. Come by tonight.”

When I arrived after sunset, I realized I had passed Chester’s house hundreds of times. It was a skinny, three-story house along the highway, right at the turnoff for the Dunwich Mine. There was a single porchlight on at on at Chester’s when I pulled, revealing the house’s siding. It was painted in Robin’s Egg blue, up against the red mine tailings and brown, muddy snow that covered the valley. It looked hideous.

A shadow opened the front door, waved.

A minute later, one duffel bag in hand, the front door closed behind me.

“You can come upstairs for the kitchen,” said Chester. He opened another door, and we headed for the basement.

“Sleeping quarters…” He flicked the light on for a cramped bedroom. The one light was a lamp that piddled out a jaundiced yellow glow. The bed had one of those Black Lagoon mattresses that you struggle to get out of. Still better than a driver’s seat.

I was led down a hallway. A door opened onto black.

“… And bathroom” said Chester. The light went on.

It was an odd choice in interior design. It was another staircase, but there was a tiny bathroom set into an alcove on the right-hand wall. There was just enough room for the toilet, a sink, the TP dispenser, and a rack for books. I made note of that. I would read a toaster manual if it kept me squatting. Beyond the bathroom, the stairs kept going down. There was no bottom, the stairs ended in darkness, a total void.

Chester sighed. “Mostly old furniture down there, and the old coal furnace, probably. You can take a stab at cleaning it when you’re ready.”

I nodded. “Sure.”

“We’ll start on the grounds tomorrow morning” said Chester. “Sleep well.” He flicked the light switch, the darkness instantly meeting me at the threshold. Chester walked off. I looked back at the stairs, flicked the lights back on, and headed for the bedroom.

In the morning, I learned the groundskeeping. The property was much bigger than it looked from the road, and contained the ruins of the first coal mine in the area. Chester said the mine was opened in 1893 by his distant Welsh ancestors. I scrubbed graffiti off the old concrete walls, checked for holes in the fence, and hunted down the invasive houndstongue weed.

The fresh air felt good. Work felt good. No, menial labor did not get things moving. If only it worked that way. At night, I moved my pillows into the bathroom and got to work. My body was pudgy mush from my condition, even climbing the mine tailing piles got me winded. At least I wasn’t homeless, and had a job. Maybe if I saved up for a few years (ugh, “saved up”), I could afford plastic surgery. That wouldn’t be such a bad life, would it?

I finished the book I’d brought with me. I was sure it’d keep me company for a month, but it had fallen like every other tome I’d tried. I dropped it into the book rack and reached for another.

My hands touched something leathery. I pulled the object out.

It was a notebook. Real leather, too, from the look of it. It was held shut by a bootlace, wrapped around a button sewn onto the cover. I untied it, and looked inside.

I found hand-written notes, in two different handwritings. It looked like some kind of guest book. Each page was packed with words scribbled in smudged black ink. Towards the end, I recognized a signature: “Shep.”

I looked up in surprise. Shep, my drinking buddy. We’d met at Delta Burgers and Taproom five years back. Before the attack, we’d tossed back cheap beer along the cliff walls every week, hollering out and letting our voices come back, Uncle Kracker playing on his Jeep’s beat-up stereo.

Come to think of it, I hadn’t seen Shep in a good minute. Had he been staying here?

I thumbed back a few pages to where that handwriting started, and began to read:

“I’ve worked for the railroad for 20 years. I’ve probably traveled a quarter-million miles, from the Puget Sound to Pensacola.

“Every conductor I’ve known worries about a derailment, or a collision. There’s one thing we fear even more. Two years ago, it happened to me.

“I was on an express freight line out on the plains, near Aroya Gulch. There’s only one crossing along that stretch. I could see the car’s brake lights a mile out. I blew the horn twice. When I got nothing, I hit the brakes, but it takes about a mile to stop a train. If the car wasn’t going to move, I couldn’t exactly swerve out of the way.

“The second before we hit the car, our front light lit it up. I’ll never forget how he was looking right at me.

“I heard they found a note, but I never heard what it said.

“Most nights, I see him looking at me. When I turn a corner in town, I see him in the other car. Sometimes I hate his rotten guts. I want to ask how he could do that to me. I try to remember he was just a kid, not in his right mind.

“Management won’t allow you to work a train if you have shell shock, or PTSD, whatever they call it. I don’t have any other skills. A buddy of mine had hit a car on the job, he gave me some of his pills. What the hell was I supposed to do? They calmed me down. Then all the bathroom stuff stopped.

“I’d go on walks at night. That’s where Chester found me. Told me to move in, keep my rent money in my pocket.

“It means a lot to me, him letting me stay here.”

I looked up from the book on my thighs, one hand over my mouth. I thought I knew Shep, but he’d never told this to me. Had this been needling away at him these past two years? All our nights watching the football games, playing eight-ball until the bar radio went quiet, and he’d never told me?

A thought passed through my head: Did you ever tell anyone?

Then a realization struck me all at once. My pain was gone. I’d forgotten it in the pages.

I looked back down. Shep had written one more line:

“What’s making that noise?”

The next afternoon, I leaned against the side of an old mine cart, trying to supress my useless urge to let loose. Chester kept the house locked up during the day, I could nap and eat lunch in a toolshed out by the mine tailings. I lapped the property three times, clipping hedges, fixing holes in the fence, making sure the mine’s old chemical ponds weren’t disturbed. All the while, the notebook remained fixed in my head. Reading that notebook was the first time in six months I felt no pain. I had to keep reading.

Back in town, the bells at the Methodist church were chiming six. I heard gravel crunching under tires. Chester was home.

I followed right behind Chester as he turned the key in the front door lock and entered the house. He paused to drop his keys in a dish by the door, I edged past him and eased my way down the stairs.

I closed the bathroom door, dropped my pants, and flopped onto the toilet. I noticed the lights had changed. If I leaned forward a bit, I could see the shadow had crept up the wall. I thought I should get some new light bulbs from the toolshed.

I flipped through the guestbook and opened it to the bootlace bookmark. Then I recognized the new handwriting and let out a sick groan.

I’d seen this handwriting at the bottom of a hundred receipts for burgers and beer. It belonged to Griff, my best friend from high school. He’d gone off to Iraq, came back a hero, now he’d been here, too?

I rolled through my last six months of memories, and the truth was a sucker punch. They were both gone. I hadn’t noticed. I was so caught up in myself. Didn’t I have good reason? I thought.

I looked down at the notebook. I expected what I knew, what everyone had read in the papers: the roadside bombing in Iraq. I was there for the parade when he returned.

I began to read…

“Dunwich has one main street, and two blocks of homes along the highway. There was a parade when I deployed, and a parade when I returned. For the deployment parade, I shook hands with the mayor and the marshal, but what I remember most is my high-school janitor. He’d watched me grow up from kindergarten, and now, tears were running down his broken-down face.

“People count on me as their pillar. If I went around talking about this, people might lose confidence. But I was sitting here in this weird bathroom, and I saw this book. I couldn’t believe old Shep wrote something in here. I dunno. Maybe it’s easier to write this stuff down, no-one but the spiders to see it.

“I’ve been hunting Pheasant along the Gunnison all my life. That paid off later in basic training, where I excelled in sharpshooting. When I’d graduated college, I had never even been to Canada.

We were providing security for an informant meeting outside of Basra. When we reached the rendezvous point, everything was horribly wrong. Part of that ‘killer instinct’ I guess, a feeling more than a checklist. It was the way the crowd at the village outskirts moved, the people watching from the rooftops. The air was heavy with anticipation.

“I saw the boy across the street. I saw the cell phone in his hand, a valuable item back then, too valuable for him to hold.

“Not a cell phone. A detonator.

“No time to give orders, no time for negotiation. I lifted my rifle and gripped the trigger. He didn’t fall backward. I saw his feet leave the ground, and then he was gone. His body landed in pieces, one arm flopped onto the dirt, the phone still untouched in his hand. I had saved us all.

“Then the bomb went off.

“I spent six months at the Balad AFB hospital. When I was conscious enough, they told me the boy was a decoy, the real trigger man was up at the roof. My CO told me the boy would have become another raghead bomber anyway. We laughed in the frigid hospital room, and then I screamed. My spine was held in place by fifty screws, and the painkillers were wearing off. The doctor said that without the screws, I’d be in the wheelchair for the rest of my life. I built back strength shuffling down the hallway, my back leaking a trail of blood and spinal fluid. When I landed back at Buckley, they had me hooked to every painkiller in the dispensary. I had no complaints.

“I left with a parade, I came home to one. I was so high when I shook hands with the mayor, the crowd seemed to be washed in tie-dye colors, doing the wave by stretching their bodies into spaghetti. They pinned a medal to my chest, and doctors put more metal in my back. Soon I could walk almost normally, but without the pills I’d wake up sweating, fists balled around my sheets, unable to sit up.

“Every day, I’d wake up and head to the bathroom. I’d look into the mirror and end up crying for twenty minutes. I’m thinking about that boy. I ripped that boy apart. I see him at work when I’m doing surveys, watching me from behind a rusted shaft entrance. I see him in the crowds when school lets out.

“There’s a sign on the highway exit for Dunwich that says ‘Home of Heroes’. If I ever told anyone this story, they’d call it ‘home of a murderer’. I’d be a football for angry editorials.

I rubbed my face and grunted. Any grief I had for my friend got boiled off by my anger. My friend, my friend! All those mornings we’d carpooled to the mine, and we’d just flapped lips about the Broncos game, and how the new coach kept screwing up. That, or we would stare off in silence. If he’d been in such pain, why didn’t he come talk to me? I could keep his secret, goddammit. Pour your heart out, Griff! I’m here for you! Let’s not waste time yukkin’ it up, asking when the first whiteout would come this winter. Why couldn’t he share his pain with me? He should have trusted his friend, why didn’t he just talk to me?

I returned to the book. I had just enough time to register Griff’s next line, scrawled in splattered ink:

“What the hell is that???”

A massive thud rose up from the dark basement, so loud my ears rang. Every vein in my body slammed shut with terror. Down in some queasy knot in my stomach, I knew that something at the bottom of those stairs was aware of me.

The book fell from my hands. I leaped off the toilet and pushed into the hallway. I braced up against the door, my chest running hot and cold.

Chester called out my name. Rapid-fire footsteps coming from the main level. I pulled up my pants just as Chester ran in with a shotgun.

“The san hill was that?” he exclaimed. “Some animal?”

Out of breath, I shook my head.

Chester lowered his gun and started to chuckle.

“Good god, call pest control! Probably a bear,” he said. “Who knows where that basement leads?” He secured the door with a deadbolt, and lifted me off the floor.

I didn’t hear anything else that night, but I couldn’t sleep. I kept thinking about that bathroom. There was something very wrong with this place. Chester said his house was built in the 1920s. The mine owners would store booze in coal tunnels, which connected to properties all over the valley. How far down did the basement go?

Chester had said it was a bear. Lying in the cramped bedroom, thinking about it, I shook my head. That was no bear. Still, whatever was at the bottom of the stairs, I had to get back in there.

That night, I had felt something for the first time in six months.

Something had moved.

I woke with a twitch. The clock’s glow-in-the-dark dials read 5:37. I crossed the hallway and undid the deadbolt. I closed the door behind me, dropped my boxers, and shivered as I touched the cold toilet seat.

My feet kicked against something. The notebook. I opened it. I needed a story. My friend’s stories helped clear my mind, but I’d read them both. I dug around in the book rack. A pen. I ran the tip across the top of a notebook page. Blue ink.

I wrote.

I wrote about driving an old RV up into the Black Canyon. I wrote about my ex’s dog getting scared by some firecrackers, and how I hunted for him beneath the RV’s undercarriage as the sunset faded.

You know the rest. I wrote about weeks spent watching TV, noticing the light cross from one side of the basement wall to the other. I wrote about pain I knew so well, that I’d miss it when it was gone. I wrote about the people who’d left me, and wondered if I’d left them, too.

The notebook took up my whole field of vision. The letters stood twenty feet high in my mind, the pen strokes were deep ditches. Someone had to know this story. I pushed out all sound. I heard the emotions of my memories. I relived each experience as the words hit the page. I was writing so someone might read it some day, someone would know they weren’t alone out there. I needed to know I wasn’t alone, either. Everything else was dead air.

Which is why I didn’t hear the crawling, and the clawing.

The corner of my eye caught the thing’s roving, searching antennae. It was not yet out of the blackness, but it was big, and looking for me, pulling a girthy, shambling mass towards the stairs. I yanked my head back into the bathroom alcove, my heart beating out of my chest.

It’s coming…

A long, hairy claw sunk into the drywall and tore a jagged gash. The antennae swept the air ahead, dancing like a fishing pole that caught a feisty one. My mouth opened, I swallowed back the scream. With one jump, I could make it to the door, but I couldn’t move.

I wouldn’t move.

It was happening.

In that moment of horror, I could manage a smile.

It was a profound feeling of lowering, releasing, change. The thing was getting closer, and it was hungry, but I gripped the toilet with white knuckles. The creature heaved itself up a step, an antenna swooped toward me.

Thuds pounded at the walls, some second half had caught up, and I could smell its steamy breath around the corner, it jaws wet and clicking.

The lowering had become a sinking, and then a slipping. I thought of the dog under the RV.

“You’re going to die” he told me.

The antennae felt their way over the alcove ceiling and began coming down towards me. I gripped my bare thighs until they bled. I opened my mouth to a silent scream… and then the agony slid away.

I wanted to collapse onto the seat and sleep for a thousand years. Instead, I shifted forward and shouldered the door open, stealing one glance at the creature and its salivating jaws. I slammed it shut with a cry.

I bolted outside, slipped on the dewy grass. My heart felt like a steam boiler about to blow, but I was laughing. It was done. The world felt new: the dew on the grass, the shiny bell tolls from the church tower, the pretty houses beneath the peaks of Mount Dunwich.

I got up with new pains behind me, and buttoned my pants up. I noted, with amusement, my own bloody hands.

I walked along the river, greeting everyone as a blessed gift, and they walked past at a faster pace. I could finally let go now. Shep and Griff had, they’d flown far from this dark and cold.

Busted face or not, I’ll join them, and I’ll think of them every day.

It’s 7 AM now, judging from the church bells. I can wash at the bus station and catch the 9 AM to Denver. For now, I’ll sit and watch the morning sunshine play on the Gunnison. It feels good to be alive, and, Lord willing, even better to be regular.

The sun burns off the fog, and I smile, with tears in my eyes.

“Thank God!” I say… “Thank the Almighty God!”

Lafayette, Colorado

March 2019

This short story is the result of many hours of hard work, to provide you with a gripping narrative experience. If you liked this story, and would like to see more like it, please consider supporting me on Patreon. As a patron, you get early access to new stories, you can vote on upcoming stories, and your name will be featured in the Patron thank-you section of future titles.

Your patronage contributes to further design improvements to this e-reader, furthers collaborations with illustrators, and allows me to hire voice talent for audiobooks.

TEXT © Nicholas Bernhard

DOWNLOAD ENTIRE E-BOOKThis e-reader was developed by Nicholas Bernhard, © 2020 - 2023 Nantucket E-Books™ LLC. Nantucket E-Books™ is built on free software, which means it respects the freedom of the writers and readers using it. For more information, check out the software license page, the Help page, or e-mail me at njb@nan